NJ In Thick Of Fight Against Trump’s Efforts To End Birthright Citizenship

By Benjamin J. Hulac

Washington Correspondent For the NJ Spotlight News

WASHINGTON — The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to issue a ruling in the next few weeks that may alter birthright citizenship, a foundational legal protection enshrined in the Constitution after the Civil War, and may make it more difficult to challenge all Trump administration policies in court.

On the evening of Jan. 20, his first day back in office, President Donald Trump signed an executive order barring children born in the U.S. from citizenship if their parents were not in the country legally or temporarily, such as through a visa.

Before that order could enter into force, immigrant advocacy groups, pregnant women and states, including New Jersey, sued to block it, ultimately securing nationwide injunctions against the order.

New Jersey is the lead plaintiff on one of the three cases that were appealed to the high court, and New Jersey’s solicitor general, Jeremy Feigenbaum, argued the case, representing 22 states and two cities: San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

Platkin confident

Standing outside the Supreme Court this month, New Jersey Attorney General Matt Platkin said he believed Feigenbaum made inroads with justices who may be swing votes.

End of birthright citizenship would generate “chaos on the ground, and I’m confident that we’re going to prevail,” Platkin said in an interview with NJ Spotlight News. “For people in South Jersey who give birth in Philadelphia, which many people do, the citizenship of your child would turn on whether you go to a hospital in South Jersey or Philadelphia.”

Whatever ruling the court issues could have cascading legal implications nationwide.

Platkin said he and his team — “We’re doing this work with a relative handful of people,” he said, gesturing to Feigenbaum and a few staffers in front of the courthouse — pursue daily law-enforcement matters, like organized crime, housing and opioid abuse, while keeping an eye on broader constitutional threats.

Federal judges in lower courts have ruled against the Trump administration, including Judge John Coughenour, a judge in Washington state nominated by the conservative Republican President Ronald Reagan, who called Trump’s order “blatantly unconstitutional.”

Major legal implications

Whatever ruling the court issues could have cascading legal implications nationwide, from who would be eligible for state and federal programs if the U.S. were to completely strip citizenship from those born here to noncitizens, to how state, local, tribal and federal officials would implement a new legal regime in which a whole group of people go from being American citizens to a murky legal status overnight.

During oral arguments, the justices appeared skeptical of the legality of Trump’s order, and the real-world consequences it would kick-start.

But they could rule on the technical half of the case and create a new standard for legal injunctions — in plain terms, a court-ordered stop — that would apply to court challenges on many topics, not just immigration policy.

The court’s current term will end in late June or early July.

Looking for signs

Justice Elena Kagan of the court’s liberal wing alluded to how national injunctions were used during the two previous presidential administrations, when plaintiffs filed cases where they might get a more sympathetic legal ear.

“In the first Trump administration, it was all done in San Francisco, and then in the next administration, it was all done in Texas, and there is a big problem that is created by that mechanism,” Kagan said.

If judges were not allowed to block President Trump’s executive order, it would affect ‘thousands of children who are going to be born without citizenship papers.’ — Justice Sonia Sotomayor

Conservative justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas appeared skeptical of one judge’s ruling being applied nationwide.

All judges, Alito said, “are vulnerable to an occupational disease, which is the disease of thinking that ‘I am right and I can do whatever I want.’”

Questioning Sauer, Thomas raised the notion that courts did not issue rulings applied nationwide — beyond the scope of just the people directly involved in a given case.

“So we survived until the 1960s without universal injunctions?” Thomas asked.

As early as 1913, the court issued injunctions against federal officials, blocking them from enforcing a “federal statute not just against the plaintiff, but against anyone” until the court rules on the case, according to a 2020 Harvard Law Review article.

Tough questions

Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh, both swing votes, had tough questions for Sauer, the government lawyer.

If Trump’s order were implemented, how would states and hospitals deal with newborns, Kavanaugh asked.

“On the day after it goes into effect — this is just a very practical question — how’s it going to work? What do hospitals do with a newborn?” Kavanaugh asked.

Sauer said that federal officials would have to figure out the implementation.

“How?” Kavanaugh asked.

“So you can imagine a number of ways that the federal officials could—,” Sauer said.

“Such as?” Kavanaugh pressed.

Liberal-leaning Justice Sonia Sotomayor also touched on the real-world impacts.

If judges were not allowed to block the order, she said, it would affect “thousands of children who are going to be born without citizenship papers.”

Knotty complications

In a brief filed with the court, lawyers for the states raised the practical implications in which kids born in some states are citizens while others born elsewhere are not.

Complicating matters, another question would emerge if a child born without citizenship moved to a state where birthright citizenship was the law of that state. Without a national injunction, this sort of piecemeal legal jumble of different legal statuses that kick in or vanish, depending on geographic boundaries, could actually happen, the states argued.

Congress in 1940 also codified birthright citizenship into federal law as a right of any child born in the U.S.

“A patchwork scheme of birthright citizenship would, in reality, only increase the States’ administrative costs and operational burdens, because they would need to track and verify not only the immigration status of a child’s parents, but also the birth state of every child to whom they provided federally funded services — as well as to develop, maintain, and train staff on different eligibility verification systems for different sets of children depending on the state of birth,” the brief says.

What the 14th Amendment says

Birthright citizenship is protected under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a right the high court upheld in 1898 when it ruled, 6-2, in the landmark case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, that nearly all children born inside the country are U.S. citizens, regardless of their parents’ immigration status.

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States,” the amendment reads.

Congress in 1940 also codified birthright citizenship into federal law as a right of any child born in the U.S.

“We are going to continue to do the work that matters to everyday New Jerseyans, but this matters too, in a state with 2 million immigrants,” Platkin said.

One citizen’s story

Melanie Machuca-Perera, 22, said her parents and three older siblings came to the U.S. from Uruguay, undocumented, in 2002.

“My mom came, didn’t know she was pregnant with twins, found out in a basement in Jersey,” Machuca-Perera, an immigration rights counselor from Elizabeth, said in an interview with NJ Spotlight News. “Six months later I was born with my twin sister.”

Because she was born in the U.S., she had access to resources, like medical care; her older siblings, born abroad, did not, forgoing visits to the dentist, she said.

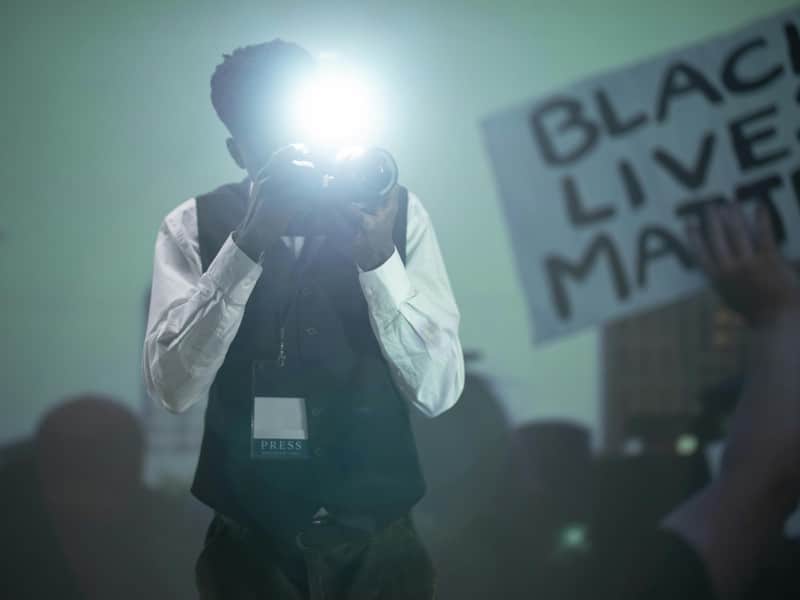

State lawyers work ‘around the clock’ as NJ challenges Trump’s orders Machuca-Perera, who traveled to protest outside the court with the group Make the Road New Jersey, said she was confident the Constitution would protect her.

“The Constitution has been here for hundreds of years,” she said. “That’s not going to change now,” she added. “It’s just that agenda that the administration has of trying to divide people.”

Trump this month said online that the U.S. is a “STUPID COUNTRY” to allow birthright citizenship.

“Birthright Citizenship was not meant for people taking vacations to become permanent Citizens of the United States of America, and bringing their families with them, all the time laughing at the ‘SUCKERS’ that we are,” he said in a post on his social-media platform.

Thirty-three countries have some sort of birthplace-based citizenship structure, though “only six of those are located outside the Americas and the Caribbean,” according to the American Immigration Council, a research group.

“I’ve never set foot in Uruguay, and if that changes, it’d be scary,” said Machuca-Perera, referring to potentially losing legal protection the Constitution guarantees.